On a delightfully sunny morning, as we followed a large walking tour through Harlem's historic streets, the sounds of construction repeatedly drowned out the orations of our informative guide.

At nearly every turn, clanging, banging and abundant Department of Buildings (DOB) certificates affixed to handsome row houses announced the renovations taking place within — all of it meant to meet the demand of buyers and renters seeking out Harlem residences in unprecedented numbers.

This latest Harlem building boom is a welcome turn for a neighborhood that has experienced more than its fair share of ups and downs. Striver's Row — the two blocks of West 138th and 139th streets between Frederick Douglass and Adam Clayton Powell Jr. boulevards — is emblematic of Harlem's rocky path to the 21st century, but its classic, revered architecture and uniquely cohesive layout have saved it for generations to come.

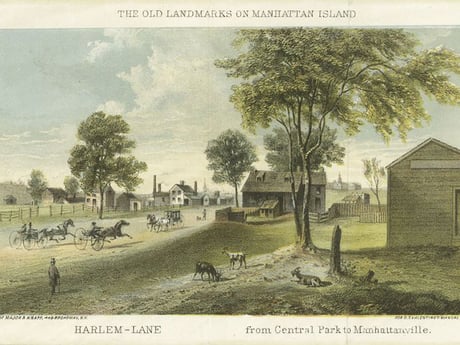

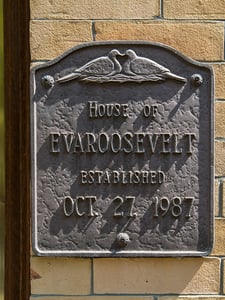

Through most of the 1800s, Harlem was an idyllic getaway for the city's elite. Gentle hills, substantial estates and bucolic farmlands dominated the region, and Harlem Lane, which ran roughly along today's Seventh Avenue, was the scene of famed carriage races that attracted the rich and famous from across the country. "The wealthiest and most prominent families in New York — Roosevelts, Astors and Vanderbilts — lived here," explained our tour guide."Harlem was Manhattan's first suburb, and visitors would travel here by boat when most people still lived below 23rd Street."

As waves of European immigrants arrived, Manhattan's population grew ever northward and the richest families moved their playgrounds to Long Island, Upstate New York and beyond. The tracts of land left in their wake, plus the arrival of elevated transit lines in the 1880s, made Harlem the site of brisk real estate speculation. In this feverish atmosphere, prominent builder David. H. King Jr. acquired the land on 138th and 139th streets in 1891 and began planning a revolutionary housing development, employing the finest finishes and a choice of architectural styles.

Dubbed the King Model Houses, the homes would be designed by the preeminent architectural firms of the day and, inspired by English urban planning, would include long alleyways behind the homes themselves. These convenient passages stretched from avenue to avenue while the street blockfronts were trisected by driveways and handsome carriage gates requesting that residents "Walk Your Horses."

Unfortunately, the development of the King Model Houses was completely out of step with the demographic and economic realities of turn-of-the-century New York City. First, the completion of the homes coincided with a number of serious economic depressions, in particular the Panics of 1893 and 1907. The well-to-do white residents and investors, for whom the homes were designed, were beginning to see their funds dry up while Harlem became less and less desirable. Moreover, King's grand vision for the development resulted in unreachable prices for the working class. Formally named the St. Nicholas Historic District, the neighborhood's official designation report highlights this notion, "The King Houses represented what was possibly the apex of that disastrous spurt of

over-investing which occurred at the end of the Nineteenth Century. It is reported that in a society whose working class families paid an average of $10-18 monthly for rent, rents for these dwellings started at just below $80."

The Equitable Life Assurance Society, which had financed the development, foreclosed on the homes in 1895. But even as Harlem's black population grew substantially, driven in large part by the great migration of black southerners, Equitable refused to rent or sell to black families. The beautiful homes remained largely vacant — or inhabited by renters with a large numbers of lodgers — until they were finally opened to black residents in 1919.

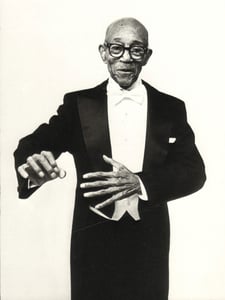

The King homes rapidly became a haven for illustrious black New Yorkers during the intellectual, cultural and creative revolution known as the Harlem Renaissance. Drawn to the prestige of living in the once-forbidden homes, prominent black residents included surgeon L.T. Wright, boxer Jack Johnson, U.S. congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr., and entertainers Hubie Blake, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, W.C Handy and Lincoln Theodore Monroe Andrew Perry, better known as Stepin Fetchit. As our tour guide pointed out, "Black people gave it the name Striver's Row because it symbolized success. Once you made it here, you had truly arrived."

Unfortunately, by the time of the Great Depression and World War II, the houses once again saw a rising number of vacancies and foreclosures. Many were pressed into service for institutional use and single room occupancy establishments. However, the special beauty of the homes seems to have been their saving grace through times of despair. Per the district's designation report, "The fact that these houses have been well maintained through the years is most unusual in New York City. Obviously, its reputation as a fashionable area has contributed to the residents' desire to preserve their home and to their tremendous sense of pride in them." Luckily, in 1967, the Landmarks Preservation Commission designated the area as the St. Nicholas Historic District, and the neighborhood was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1975.

Despite the use of three different architecture firms, similar proportions and overall style makes the blocks of Striver’s Row uniform without being monotonous. In fact, one could envision several more blocks of this type extending in all directions to delightful effect.

On the south side of 138th Street, red brick and brownstone houses were designed in the Georgian style by James Brown Lord. The Lord houses, at 22-feet wide, are the widest homes in Striver's Row and feature handsome L-shaped stoops and details both bold (splayed lintels with dominant keystones) and delicate (egg-and-dart decoration around parlor level windows and doors, and lovely dentilled cornices). By far the most colorful facades in Striver's Row, here, deep brownstone contrasts nicely against red brick with black iron handrails running along street level and green hued cornices above.

The northernmost portion of Striver's Row runs along the upper edge of 139th Street where the famed McKim, Mead and White firm designed 32 Italian Renaissance homes. The consistent brick and brownstone treatment of this row creates a visual consistency that tends to conceal the fair amount of variation at work in the design, especially when comparing the center homes to those at either end. These homes include charming Juliet balconies and the only small front gardens in all of Striver’s Row.

Architects Bruce Price and Clarence S. Luce were given the privilege of designing two blocks of homes within the King project, and their work runs along the north side of 138th Street and the south side of 139th. Constructed in buff brick with pale Indiana limestone and terracotta ceramic, the Georgian-style homes have a stately and serene beauty. Fine details are abundant throughout their charming facades with carved splayed lintels with elongated keystones decorating the parlor floor windows and doors, while upper floors include dramatic lintels with semi-circular panels. Classic garland, swag and wreath motifs abound, while wrought iron Juliet balconies and handrails create a delicate, yet bold statement against the light-colored facades.

Two Dixon homes are among the handsome Price & Luce rows, one with gorgeous original detail and another with a more modern aesthetic.

According to Dixon Senior Project Manager Megan Eisenberg, the home at 261 West 138th Street had plenty of details that were preserved before the renovation, including moldings, entablatures over the entryways, fireplace mantels, the front entry doors and interior pocket doors. Painstaking effort went into restoring other elements to their former glory, such as creating replacements for missing finials and spindles on the staircase and calling upon Artistic Tile to recreate missing tiles around the fireplace hearths.

Where original elements were missing or unable to be restored, effort was put into matching the style and spirit of the original finishes. "I went on a historical tour of the homes of Striver's Row and was able to get a nice understanding of the preservation of these properties," Eisenberg explains. "Typical of how these houses were created, we did flooring in the parlor area on the diagonal, which is one of the details I picked up on the tour." In addition to the flooring, light fixtures and bathroom finishes were chosen in classic styles similar to the tradition of the home's era.

The layout at 261 West 138th has also been kept largely to the original plan. The parlor floor welcomes guests with grand double doors opening to reception areas that give way to a unique two-sided fireplace and ample millwork. At the rear, an entirely modernized kitchen, now complete with top-of-the-line appliances, leads past a powder room to a large roof deck. On the upper two levels, three large bedrooms include custom closets and en suite bathrooms, while a fourth bedroom houses another grand fireplace and small terrace. The large garden level includes a fifth bedroom, large family room and a well-appointed laundry room that leads to the homes prized garage, which can be conveniently accessed from the rear alleyway.

Just to the east, the Dixon home at 233 West 138th Street offered the team fewer original details to work with, which opened the door for a more modern interpretation. Here, the parlor floor is dominated by pale finishes that echo the coveted buff exteriors of the Price & Luce row. Reception rooms open to a thoroughly contemporary kitchen with swaths of marble and polished chrome fixtures, while a powder room and laundry closet lead to a cozy den.

In this home, the second level is devoted to an enviable full-floor master retreat with a large private deck, while twin bedroom suites occupy the third floor. Up top, an innovative skybox skylight by England-based Glazing Vision adds low-profile access to another large roof deck and floods the staircase below with natural light. Skyboxes are especially important when adding roof access in historic districts that prohibit additional structures that would be visible from the street. Now, instead of a challenging hatch-door access point, residents can ascend the home's staircase and take in sweeping Upper Manhattan views from the expansive deck.

On the basement level, a fourth bedroom suite, large rec room and wet bar provide the perfect spot for indoor entertaining and relaxing.

Similar to its 1800s heyday, Harlem is becoming recognized for its tranquil beauty and the Dixon Leasing portfolio contains a number of residences in the area, including two new additions that are nearly complete. As our tour guide remarks above the sounds of construction, "Harlem is one of the prettiest places in New York, and everyone wants to be here."

201 366 8692

201 366 8692